A friend of mine pointed out a recent talk by John Hughes that describes a how Volvo is using Erlang and more in particular Quickcheck to find bugs in automotive software systems. While the talk is rather boring the topic is actually quite fascinating! And since I’m … let’s say acquainted with the automotive industry, it’s especially good to see a company like Volvo picking up on some modern software ideas.

I’ve long had a affection for Quickcheck as it is the testing tool of choice for testing haskell programs. But in my day job I mostly do embedded programming in C++, in an environment where errors are hardly tolerated. Having a solid suite of unit tests in place can go a long way in ensuring the expected program behavior. And since I like testing this is actually fun to do.

Quickcheck allows for quite a different approach to testing: you need to formulate properties of a program and that Quickcheck can then verify them for you by generating valid but random input data and automatically checking the properties for this input. This is one of the reasons why I love programming in haskell. Once you get the hang of it you will not want to miss it anymore.

Need for extensive Testing

For a recent project I had to implement a service in C++ that could be used by a number of different clients whose operation depends on the current voltage level of the battery they are running on. Those clients need to react properly if the voltage drops below a certain level or exceeds an upper threshold. Seems to be pretty straight forward. But as always there are details that complicate matters:

Complicating Requirements

- Registration: clients are allowed to register and unregister during all times

- Threshold: each client can specify her own levels for either a lower threshold, an upper threshold, or both

- Timeouts: clients can configure a timeout to specify how long an such an exceptional situation would need to prevail in order to get a notification

- Hysteresis: when recovering from over/under-voltage clients can specify an hysteresis to prevent a situation where it would be notified too often when the voltage level drifts around the trigger level

- …

When implementing something like this service I tend to do a lot of unit-testing to verify correct behavior. But when the parameters of the system under test become too many it will soon become impractical to cover all possible situations with an unit-test. This is actually some indication that now will trigger my quickcheck-infiltrated brain to begin formulating properties of the system, e.g.

- circumstances under which clients will definitely have received notification

- situations in which a client that is registered will not be notified when the voltage crosses the threshold

- invariants considering the (de-)registration

- …

Quickcheck to the Rescue

Quickcheck is a valuable companion when it comes to generating a sequence of inputs that will surface weak spots in the implementation. In case of such a control-system, the inputs are actually a series of events like

- a change in the voltage level

- a registration or de-registration of a client

- a timeout event that will trigger client notification

A stream of events will describe the behavior of the system over time. And this is what we can use to bring in Quickcheck.

Defining some data-types and a way to generate valid random data for those types will be necessary to enable Quickcheck to work it’s magic and find some nasty test series that will stress the system.

Let’s say we want to check the system behavior when the current is slowly rising. So we need to generate some random event stream that simulates an increasing voltage while different clients with random timeouts randomly register and unregister. So first thing that is needed is a way to generate those clients. That can be done by defining an Arbitrary instance for clients:

data VoltageListener = VL (Int,Int,Int) deriving (Eq,Ord,Show)

instance Arbitrary VoltageListener where

arbitrary = do

threshold <- choose (5000,10000)

debounce <- elements [0,100]

hyst <- elements [0,100..500]

return $ VL (threshold,debounce,hyst)With that in place we now can define Arbitrary instances for different streams, e.g. for a rising voltage (see VoltageTests.hs for more details):

data SlowRisingCurve = SlowRising [VoltageListener] [Event] deriving (Show)

instance Arbitrary SlowRisingCurve where

arbitrary = do

vs <- eventList 350 5000 (2,1) [100..150]

listener <- arbitrary

return $ SlowRising listener (cutAfter (>12500) vs)

eventList :: Int -> Int -> (Int,Int) -> [Int] -> Gen [Event]

...

cutAfter :: (Int -> Bool) -> [Event] -> [Event]

...Letting Quickcheck work it’s Magic

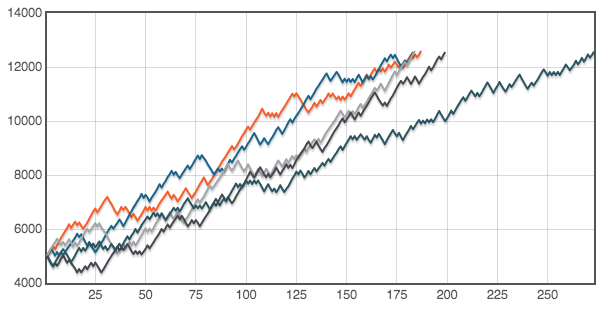

Let’s see what kind of events will be generated by quickcheck:

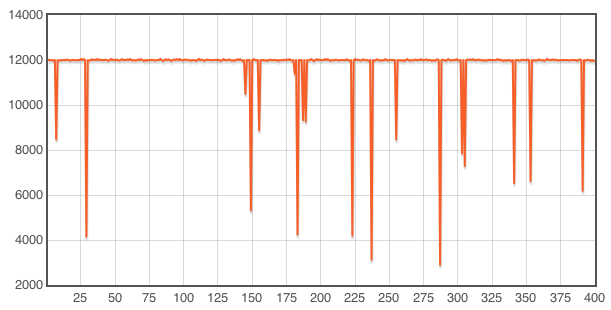

Not too bad. But what else is a realistic scenario? Maybe one where the voltage level stays more or less the same but has some occasional drops due to some loads that are put in the circuit.

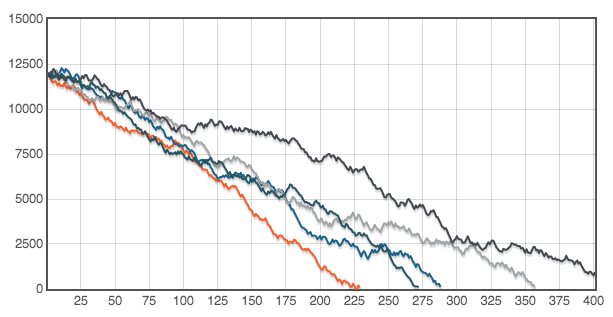

Also quite realistic is the simulation of a bleeding battery where the current slowly approaches zero.

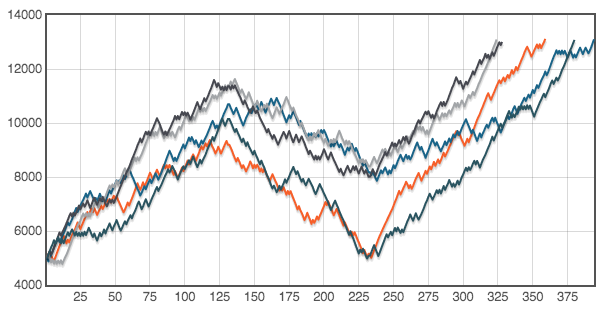

And here is one that simulates a battery that is getting charged with a pause in between.

Connecting Haskell to C++

Linking Issues

It can be a little tricky to have ghc link all the code, especially with C++ since the C++ runtime is also needed (don’t forget the -lstdc++ and -lc++ as linker flags for ghc). What works best for me is to build static libraries for the C++ code I want to test, for the C wrappers and test drivers, and tell ghc to link those.

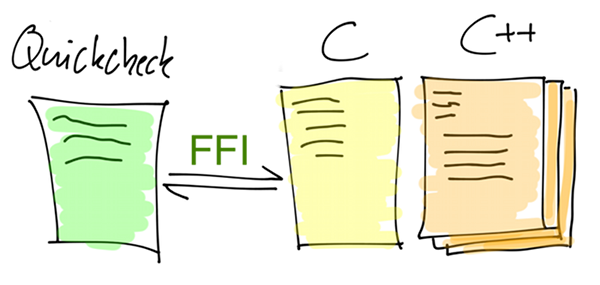

So far so good…but since there is no C++ version of Quickcheck, the task remains to bridge the Quickcheck testing facilities with the C++ code that needs to be tested. So in the final setup it is desirable to call the C++ code from haskell, using haskell as the test driver that is testing the C++ functionality. This can easily be achieved by using the FFI, haskell’s way to connect with native code.

In the simplest case we just need to call a C-function that only takes primitive types as arguments and only returns primitive types (VoltageFFI.hs).

foreign import ccall "ftest.h voltageEvent"

c_voltageEvent :: CInt -> IO ()The corresponding function in the C-wrapper then looks like this (c_interface.h):

extern "C" void voltageEvent(int);

void voltageEvent(int);Here it is important to declare the C-functions as extern 'C' to avoid name mangling in the C++ compiler and allow haskell to find the symbol. In the implementation the final call the the C++ code can now be issued. (c_interface.cpp)

class TestExecuter {

public:

...

VoltageManager voltageManager;

};

TestExecuter& getTestExecuter() {

if (!pTestExecuter) { pTestExecuter = new TestExecuter(); }

return *pTestExecuter;

}

// implementation of FFI

void voltageEvent(int x) {

getTestExecuter().voltageManager.voltageChanged(x);

}Formulating Properties

The only thing missing in the mix are the actual tests that we want to run. In Quickcheck this is done by formulating properties. Each property takes a datatype that is an instance of the Arbitrary typeclass so that quickcheck knows how to generate usecases. It’s very handy that the generated testinputs can further be restricted in the properties (e.g. we only want inputs that specify at least one listener). And finally it’s important to use the monadic interface of Quickcheck since the code we are testing is only available through FFI and therefore lives in the IO Monad.

prop_neverMissLeftUndervoltage (SlowRising listeners events) =

length listeners > 0 ==> monadicIO $ do

run $ forM_ listeners addListenerC

run $ mapM sendEvent events

forM_ [0..length listeners - 1] $ \n -> do

(finalState,enteredCount,leftCount) <- run $ voltageStateC n

assert $ finalState == normal_voltage

assert $ enteredCount == leftCount

run c_tearDown

main = do

quickCheck prop_neverMissLeftUndervoltage

quickCheck ...With this basic setup it’s now straight forward to implement the code for the quickcheck test-driver on the C++ side. Quickcheck will generate event-sequences like [VoltageUpdate, AddListener, VoltageUpdate, VoltageUpdate, Timeout, VoltagUpdate, AddListener, RemoveListener,…].

Using the C-wrapper these events will end up triggering the C++ implementation. After a series of events has been executed we examine the state of the C++ world and assert that everything matches our expectations … and see the beloved output from Quickcheck:

+++ OK, passed 100 tests. +++ OK, passed 100 tests. +++ OK, passed 100 tests. +++ OK, passed 100 tests. ...

Is it worth the Effort?

Turned out that I really missed some corner cases in my implementation where timeouts where prematurely discarded. After all, Quickcheck does indeed turn up very unexpected usecases that are still valid! And like John Hughes does with Erlang it is very much possible to use Quickcheck in haskell for testing native components!